W takim ekstremalnym przypadku lepiej najpierw zastanowić się, jakie jest zalecane rozwiązanie SQL, a następnie zaimplementować je w SQLAlchemy – nawet przy użyciu surowego SQL, jeśli zajdzie taka potrzeba. Jednym z takich rozwiązań jest utworzenie tabeli tymczasowej dla key_set dane i ich wypełnienie.

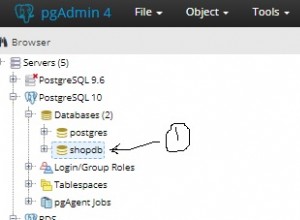

Aby przetestować coś takiego jak twoja konfiguracja, stworzyłem następujący model

class Table(Base):

__tablename__ = 'mytable'

my_key = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

i wypełnij go 20 000 000 wierszy:

In [1]: engine.execute("""

...: insert into mytable

...: select generate_series(1, 20000001)

...: """)

Stworzyłem również pomocników do testowania różnych kombinacji tabel tymczasowych, wypełniania i zapytań. Zwróć uwagę, że zapytania korzystają z tabeli Core, aby ominąć ORM i jego maszynerię – wpływ na czasy i tak byłby stały:

# testdb is just your usual SQLAlchemy imports, and some

# preconfigured engine options.

from testdb import *

from sqlalchemy.ext.compiler import compiles

from sqlalchemy.sql.expression import Executable, ClauseElement

from io import StringIO

from itertools import product

class Table(Base):

__tablename__ = "mytable"

my_key = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

def with_session(f):

def wrapper(*a, **kw):

session = Session(bind=engine)

try:

return f(session, *a, **kw)

finally:

session.close()

return wrapper

def all(_, query):

return query.all()

def explain(analyze=False):

def cont(session, query):

results = session.execute(Explain(query.statement, analyze))

return [l for l, in results]

return cont

class Explain(Executable, ClauseElement):

def __init__(self, stmt, analyze=False):

self.stmt = stmt

self.analyze = analyze

@compiles(Explain)

def visit_explain(element, compiler, **kw):

stmt = "EXPLAIN "

if element.analyze:

stmt += "ANALYZE "

stmt += compiler.process(element.stmt, **kw)

return stmt

def create_tmp_tbl_w_insert(session, key_set, unique=False):

session.execute("CREATE TEMPORARY TABLE x (k INTEGER NOT NULL)")

x = table("x", column("k"))

session.execute(x.insert().values([(k,) for k in key_set]))

if unique:

session.execute("CREATE UNIQUE INDEX ON x (k)")

session.execute("ANALYZE x")

return x

def create_tmp_tbl_w_copy(session, key_set, unique=False):

session.execute("CREATE TEMPORARY TABLE x (k INTEGER NOT NULL)")

# This assumes that the string representation of the Python values

# is a valid representation for Postgresql as well. If this is not

# the case, `cur.mogrify()` should be used.

file = StringIO("".join([f"{k}\n" for k in key_set]))

# HACK ALERT, get the DB-API connection object

with session.connection().connection.connection.cursor() as cur:

cur.copy_from(file, "x")

if unique:

session.execute("CREATE UNIQUE INDEX ON x (k)")

session.execute("ANALYZE x")

return table("x", column("k"))

tmp_tbl_factories = {

"insert": create_tmp_tbl_w_insert,

"insert (uniq)": lambda session, key_set: create_tmp_tbl_w_insert(session, key_set, unique=True),

"copy": create_tmp_tbl_w_copy,

"copy (uniq)": lambda session, key_set: create_tmp_tbl_w_copy(session, key_set, unique=True),

}

query_factories = {

"in": lambda session, _, x: session.query(Table.__table__).

filter(Table.my_key.in_(x.select().as_scalar())),

"exists": lambda session, _, x: session.query(Table.__table__).

filter(exists().where(x.c.k == Table.my_key)),

"join": lambda session, _, x: session.query(Table.__table__).

join(x, x.c.k == Table.my_key)

}

tests = {

"test in": (

lambda _s, _ks: None,

lambda session, key_set, _: session.query(Table.__table__).

filter(Table.my_key.in_(key_set))

),

"test in expanding": (

lambda _s, _kw: None,

lambda session, key_set, _: session.query(Table.__table__).

filter(Table.my_key.in_(bindparam('key_set', key_set, expanding=True)))

),

**{

f"test {ql} w/ {tl}": (tf, qf)

for (tl, tf), (ql, qf)

in product(tmp_tbl_factories.items(), query_factories.items())

}

}

@with_session

def run_test(session, key_set, tmp_tbl_factory, query_factory, *, cont=all):

x = tmp_tbl_factory(session, key_set)

return cont(session, query_factory(session, key_set, x))

Dla małych zestawów kluczy proste IN Twoje zapytanie jest mniej więcej tak szybkie jak inne, ale przy użyciu key_set ze 100 000 więcej zaangażowanych rozwiązań zaczyna wygrywać:

In [10]: for test, steps in tests.items():

...: print(f"{test:<28}", end=" ")

...: %timeit -r2 -n2 run_test(range(100000), *steps)

...:

test in 2.21 s ± 7.31 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 2 loops each)

test in expanding 630 ms ± 929 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 2 loops each)

test in w/ insert 1.83 s ± 3.73 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 2 loops each)

test exists w/ insert 1.83 s ± 3.99 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 2 loops each)

test join w/ insert 1.86 s ± 3.76 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 2 loops each)

test in w/ insert (uniq) 1.87 s ± 6.67 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 2 loops each)

test exists w/ insert (uniq) 1.84 s ± 125 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 2 loops each)

test join w/ insert (uniq) 1.85 s ± 2.8 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 2 loops each)

test in w/ copy 246 ms ± 1.18 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 2 loops each)

test exists w/ copy 243 ms ± 2.31 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 2 loops each)

test join w/ copy 258 ms ± 3.05 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 2 loops each)

test in w/ copy (uniq) 261 ms ± 1.39 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 2 loops each)

test exists w/ copy (uniq) 267 ms ± 8.24 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 2 loops each)

test join w/ copy (uniq) 264 ms ± 1.16 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 2 loops each)

Podnoszenie key_set do 1 000 000:

In [11]: for test, steps in tests.items():

...: print(f"{test:<28}", end=" ")

...: %timeit -r2 -n1 run_test(range(1000000), *steps)

...:

test in 23.8 s ± 158 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 1 loop each)

test in expanding 6.96 s ± 3.02 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 1 loop each)

test in w/ insert 19.6 s ± 79.3 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 1 loop each)

test exists w/ insert 20.1 s ± 114 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 1 loop each)

test join w/ insert 19.5 s ± 7.93 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 1 loop each)

test in w/ insert (uniq) 19.5 s ± 45.4 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 1 loop each)

test exists w/ insert (uniq) 19.6 s ± 73.6 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 1 loop each)

test join w/ insert (uniq) 20 s ± 57.5 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 1 loop each)

test in w/ copy 2.53 s ± 49.9 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 1 loop each)

test exists w/ copy 2.56 s ± 1.96 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 1 loop each)

test join w/ copy 2.61 s ± 26.8 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 1 loop each)

test in w/ copy (uniq) 2.63 s ± 3.79 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 1 loop each)

test exists w/ copy (uniq) 2.61 s ± 916 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 1 loop each)

test join w/ copy (uniq) 2.6 s ± 5.31 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 2 runs, 1 loop each)

Zestaw kluczy 10 000 000, COPY tylko rozwiązania, ponieważ inni zjedli całą moją pamięć RAM i przechodzili wymianę przed śmiercią, sugerując, że nigdy nie skończą na tej maszynie:

In [12]: for test, steps in tests.items():

...: if "copy" in test:

...: print(f"{test:<28}", end=" ")

...: %timeit -r1 -n1 run_test(range(10000000), *steps)

...:

test in w/ copy 28.9 s ± 0 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 1 run, 1 loop each)

test exists w/ copy 29.3 s ± 0 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 1 run, 1 loop each)

test join w/ copy 29.7 s ± 0 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 1 run, 1 loop each)

test in w/ copy (uniq) 28.3 s ± 0 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 1 run, 1 loop each)

test exists w/ copy (uniq) 27.5 s ± 0 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 1 run, 1 loop each)

test join w/ copy (uniq) 28.4 s ± 0 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 1 run, 1 loop each)

Tak więc dla małych zestawów kluczy (~100 000 lub mniej) nie ma znaczenia, czego używasz, chociaż użyj rozwijanego bindparam jest wyraźnym zwycięzcą pod względem czasu w porównaniu do łatwości użytkowania, ale w przypadku znacznie większych zestawów możesz rozważyć użycie tabeli tymczasowej i COPY .

Warto zauważyć, że dla dużych zestawów plany zapytań są identyczne, jeśli używa się unikalnego indeksu:

In [13]: print(*run_test(range(10000000),

...: tmp_tbl_factories["copy (uniq)"],

...: query_factories["in"],

...: cont=explain()), sep="\n")

Merge Join (cost=45.44..760102.11 rows=9999977 width=4)

Merge Cond: (mytable.my_key = x.k)

-> Index Only Scan using mytable_pkey on mytable (cost=0.44..607856.88 rows=20000096 width=4)

-> Index Only Scan using x_k_idx on x (cost=0.43..303939.09 rows=9999977 width=4)

In [14]: print(*run_test(range(10000000),

...: tmp_tbl_factories["copy (uniq)"],

...: query_factories["exists"],

...: cont=explain()), sep="\n")

Merge Join (cost=44.29..760123.36 rows=9999977 width=4)

Merge Cond: (mytable.my_key = x.k)

-> Index Only Scan using mytable_pkey on mytable (cost=0.44..607856.88 rows=20000096 width=4)

-> Index Only Scan using x_k_idx on x (cost=0.43..303939.09 rows=9999977 width=4)

In [15]: print(*run_test(range(10000000),

...: tmp_tbl_factories["copy (uniq)"],

...: query_factories["join"],

...: cont=explain()), sep="\n")

Merge Join (cost=39.06..760113.29 rows=9999977 width=4)

Merge Cond: (mytable.my_key = x.k)

-> Index Only Scan using mytable_pkey on mytable (cost=0.44..607856.88 rows=20000096 width=4)

-> Index Only Scan using x_k_idx on x (cost=0.43..303939.09 rows=9999977 width=4)

Ponieważ tabele testowe są trochę sztuczne, mogą używać tylko skanów indeksu.

Na koniec, dla przybliżonego porównania, czasy dla metody „pieszego”:

In [3]: for ksl in [100000, 1000000]:

...: %time [session.query(Table).get(k) for k in range(ksl)]

...: session.rollback()

...:

CPU times: user 1min, sys: 1.76 s, total: 1min 1s

Wall time: 1min 13s

CPU times: user 9min 48s, sys: 17.3 s, total: 10min 5s

Wall time: 12min 1s

Problem polega na tym, że użycie Query.get() koniecznie zawiera ORM, podczas gdy oryginalne porównania nie. Mimo to powinno być dość oczywiste, że oddzielne podróże w obie strony do bazy danych drogo kosztują, nawet w przypadku korzystania z lokalnej bazy danych.